The Grades Are In: A Report Card on Canada’s Progress in Protecting its Land and Ocean

Introduction and Background

The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) assessed how well Canada fared in delivering on its promise to protect 17% of its land and 10% of its ocean by the end of 2020, including the degree to which federal, provincial, and territorial governments each contributed to this shared goal. Our Report Card assigns grades to each government based on its contributions and highlights key successes and shortcomings.

It is important to recognize that the 17% and 10% targets approved by the international community in 2010 were just milestones towards what is ultimately needed to conserve biodiversity. Evidence shows that protecting between 30-70% of the Earth’s land and ocean will likely be needed to reverse the decline of biodiversity and sustain a healthy planet. Canada is currently committed to protecting 25% of its land and ocean by 2025, on the way to 30% by 2030.

CPAWS is committed to helping Canada meet its targets by supporting the creation of effective protected area networks across the country. Using our first report card as a baseline, we plan to release subsequent Report Cards to track progress made towards the 2025 and 2030 targets.

Join the movement to protect at least 30% of Canada’s land and ocean by 2030.

Read the Report Card | Read the Press Release | Read Our Roadmap to 2030

How are Canada and its Provinces and Territories Doing?

Executive Summary

The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) has conducted an assessment of how well Canada fared in delivering on a promise that dates back to 2010: to protect at least 17% of its land and 10% of its ocean by 2020. This report card presents our key findings. It assigns grades to the current federal, provincial, and territorial governments based on their contributions and highlights major achievements and shortcomings. Our goal in producing this report card is to learn from the successes and failures of the past decade to inform more effective conservation action moving forward. Using this report as a baseline, we plan to release subsequent report cards to track progress made by each jurisdiction towards the 2025 and 2030 targets of protecting 25% of land and ocean and 30% of land and ocean, respectively.

[expand title=”Read More …”]Habitat loss and fragmentation from human activities are the primary causes of the current rapid decline of biodiversity and the resulting Nature Emergency. Well-designed and managed protected areas are scientifically proven to be effective in conserving nature. Protected areas also play an important role in our well-being and the economy, making them a critical investment for ensuring a healthy and happy future for all Canadians. While significant, the 17% and 10% targets approved by the international community in 2010 were just milestones towards what is ultimately needed to conserve biodiversity: protecting at least half of the Earth’s land and ocean ecosystems.

Canada met the 10% ocean protection target by 2020 with 13.8% protected, albeit with concerns about the quality of conservation measures in some areas. However, the 17% terrestrial target was missed by a significant margin, with only 13.1% of land and freshwater protected. The report card assesses federal, provincial, and territorial governments on their contributions to the terrestrial target. For the ocean component we only assessed the federal government because most marine activities are under federal jurisdiction, and federally designated marine protected areas are the primary conservation tool for ocean ecosystems.

Our results are organized into four categories: Leaders (A- to B+), Mixed Review (B to C-), Laggards (D to F), and Notable Efforts (B-).

The Government of Quebec, the federal government, and the Government of the Northwest Territories form the Leaders group. Quebec publicly committed to the 17% target and delivered 16.7% by creating new protected areas.* In addition, Quebec also amended its protected areas legislation to recognize Indigenous-led protected areas and to commit to international standards for protection. The province received an A- because it failed to establish protected areas proposed for southern Quebec due to industrial interests.

The federal government also earned an A- for terrestrial conservation by committing to deliver on the 17% target, convening provinces and territories to work together through the Pathway to Canada Target 1 process, making two historic conservation investments, supporting Indigenous-led conservation, and committing to ambitious protection targets for the next decade. Weaknesses in how the 2018 federal funding was allocated, the lack of long-term investment, and problems with protected area management lowered the grade.

The Government of the Northwest Territories earned a B+ for passing protected areas legislation that recognizes and supports Indigenous protected areas and international standards, and for working with federal and Indigenous governments to establish protected areas. While it did not quite meet the 17% target, the territorial government made significant headway and set the stage for further progress.

For its efforts to protect Canada’s coastal and ocean ecosystems, the federal government scored a B+. Over the past five years it made substantial progress in establishing new marine protected areas (MPAs) and met the 10% target, announced minimum protection standards for MPAs, and made an historic budget investment as well as a commitment to ambitious protection targets for the next decade. Significant weaknesses in protection standards and the lack of progress on implementing minimum standards and Indigenous-led conservation lowered the grade.

The Governments of Nova Scotia, British Columbia, and Manitoba show varying degrees of promise, but still have a lot of work ahead. Nova Scotia made progress over the past decade, establishing more than 200 protected areas, including 91 just within the past year. The province faltered, however, by delisting Owls Head Provincial Park Reserve and being slow to fully implement its parks and protected areas plan. Once a leader on nature conservation, British Columbia has demonstrated limited progress over the past decade. The province reported 4% of its land base as OECMs, including existing Old Growth Forest Management Areas, thus reaching the 17% target on paper, but with many of its Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs), falling short of Canadian and international standards. On a positive note, British Columbia’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which embeds the UN Declaration in provincial law, was passed, and in 2021 the province invested $83 million in park management. While Manitoba created a $102 million conservation trust in 2018, worrying signs have emerged recently that the province may divest of some of its park assets and/or decommission or transition parks to other models. For example, campsite fees tripled at St. Ambroise Provincial Park after a private company was recently awarded a 21-year lease.

The Governments of Saskatchewan, Alberta, Ontario, and Newfoundland and Labrador received the lowest grades, ranging from D to F. Although most achieved some increases in coverage, this was largely under previous governments and, in the case of Newfoundland and Labrador, through the completion of new federal protected areas. These four jurisdictions demonstrated little or no commitment to protecting more of their land base. In Ontario and Alberta, this lack of interest is coupled with serious harmful anti-conservation action, including rolling back nature protection policies and legislation and proposing the delisting of protected areas.

The Governments of New Brunswick and Yukon remain far behind the leaders but earned B- grades, as they have recently demonstrated significant effort and are showing positive trends. Once a laggard, in 2019 New Brunswick committed to double the extent of its protected areas system and is now working with Indigenous Nations and the public to identify new protected areas. Although the percentage of land protected in the Yukon has not increased since 2010, land use planning is back on track and a final decision has been made to permanently protect 55% of the Peel River Watershed, which will result in a significant leap forward in total area protected.

Key Takeaway Messages

- Where there is a (political) will, there is a way. Quebec’s progress demonstrates what strong political will combined with Indigenous leadership and public support can achieve.

- Indigenous leadership drives success. The most consistent trend that we observed across all jurisdictions is the critical role that Indigenous Peoples are playing in advancing conservation in Canada.

- Federal funding can be a game-changer. Federal funding for conservation partners, including Indigenous, provincial, and territorial governments, and NGOs, has leveraged additional investment from the philanthropic community, and moved the dial on conservation considerably in just a few years.

- Proactive and coordinated efforts help build momentum. Progress on terrestrial protected area establishment noticeably increased after 2017, aligned with the launch of the Pathway to Target 1 and associated processes.

- Conservation takes time. A major barrier to delivering on the 17% terrestrial target was the lack of time between 2018, when the federal government committed significant funding to deliver on the target, and the 2020 deadline. Delivering on the goal of 30% protection by 2030 will require starting the work now.

- Do not cut corners with Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs). Although OECMs that meet standards may be valuable in some circumstances, protected areas, including Indigenous Protected Areas, should remain the core conservation tool for delivering on the next decade’s targets.

* In December 2020, the government of Quebec announced it had reached the 17% target. However, CPAWS has identified that only 16.7% has actually been protected and is encouraging the Quebec government to quickly address this shortfall.

[/expand]Federal Government – Land and Freshwater

Grade: A-

The federal government has demonstrated strong national and international leadership and commitment, supported and elevated Indigenous-led conservation, made two historic budget investments, and committed to more ambitious targets for the next decade. However, long-term funding to manage protected areas remains as a gap to be filled, and management of national parks and national wildlife areas is a concern in some areas.

Federal Government – Ocean

Grade: B+

After a slow start, Canada has made considerable progress on marine protection over the past six years – from less than 1% protection in 2015 to 13.8% in 2019, exceeding the international target of protecting 10% by 2020. To meet this target, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has developed new tools and approaches to expedite marine protected areas establishment and to implement minimum protection standards in all federal Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

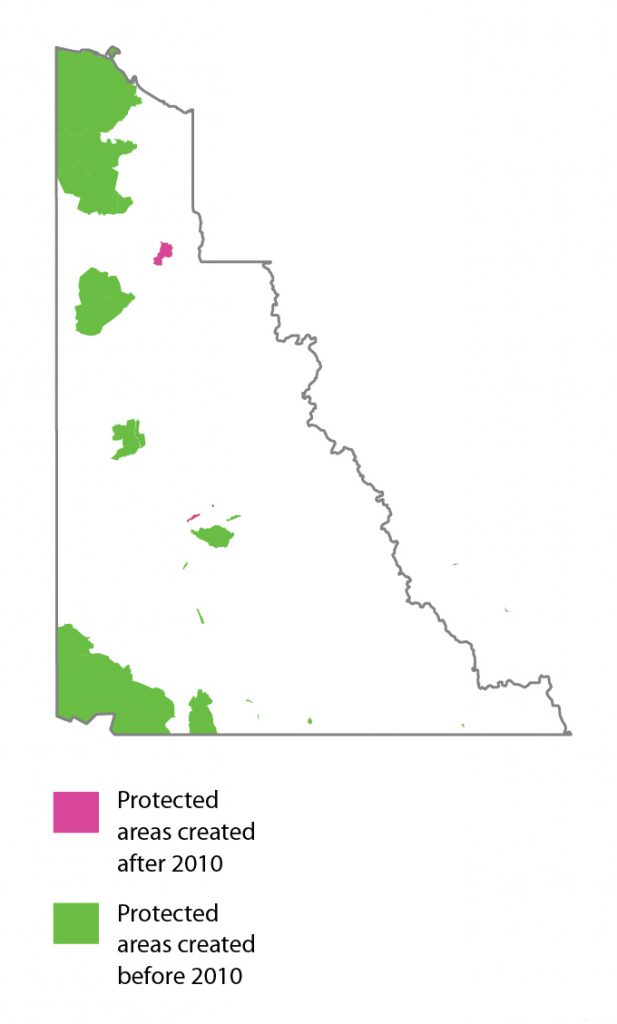

Yukon Territory

Grade: B-

The Yukon Government’s performance on protected areas over the past decade has been mixed. While three small Habitat Protection Areas were established, the regional land use planning process, one of the territory’s main pathways for creating protected areas, was largely stalled. Planning resumed following a successful legal challenge, where First Nations and environmental groups took the government to the Supreme Court of Canada to undo its attempt to undermine the planning process for the Peel Watershed. Sustained First Nations’ leadership finally led to the approval of the Peel Watershed Regional Land Use Plan in 2019, which will protect 37,000 km2 of the wild northern watershed (7.7% of the territory). An additional 28% of the watershed will have interim protection, to be reviewed after a decade.

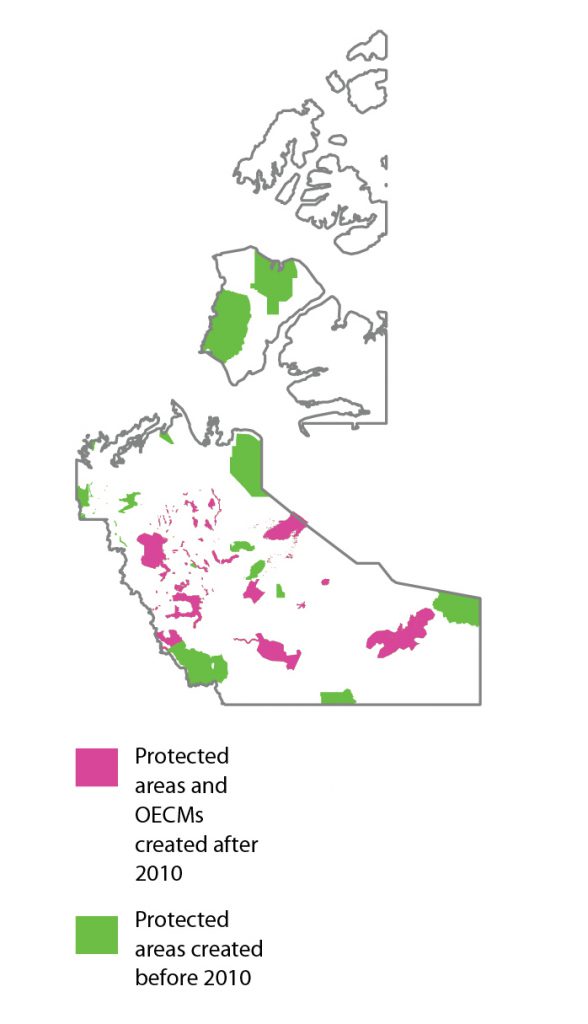

Northwest Territories

Grade: B+

Since 2018, four Indigenous protected areas have been established in the Northwest Territories (NWT), covering 4.5% of the territories. Indigenous Guardians programs have been created to support management. This progress was largely the result of longstanding Indigenous leadership, investments from the federal Nature Fund, and a new territorial Protected Areas Act developed collaboratively by Indigenous governments and the GNWT, which has goals of protecting ecological integrity, cultural continuity, and collaborative governance.

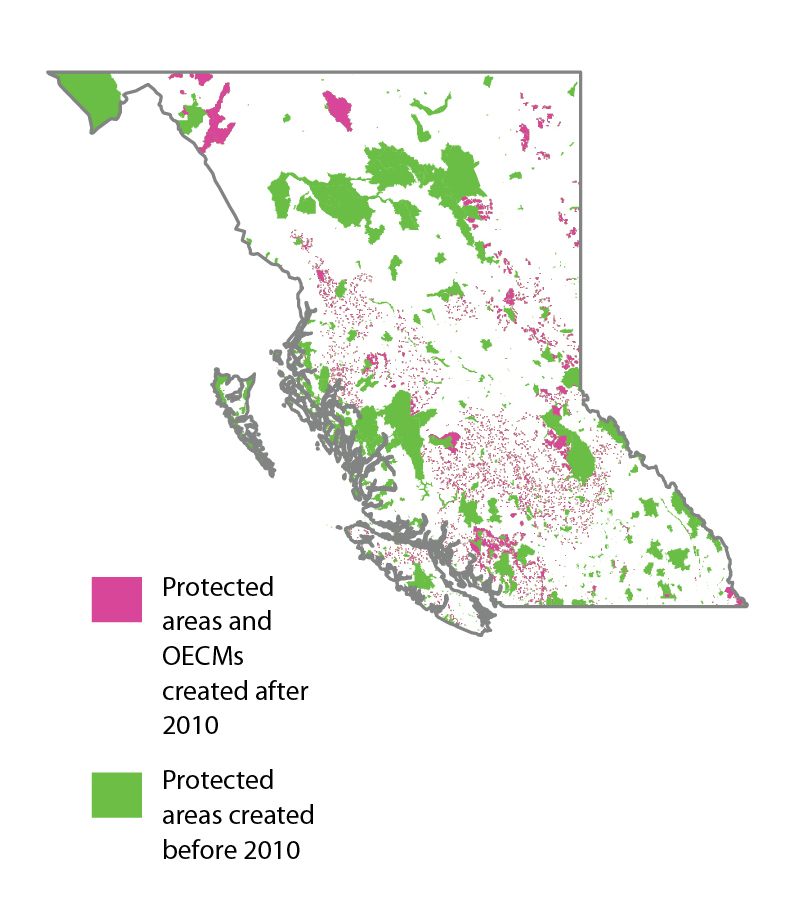

British Columbia

Grade: C

British Columbia started the decade with the highest percentage of land protected of any Canadian jurisdiction; however, since 2010, only 1% has been added. B.C. reports an additional 4% of the land base as Other Effective Conservation Measures (OECMs), which are now under review by the provincial government. B.C. includes designations such as Old Growth Management Areas, which fall short of both international and Canadian standards for OECMs. This detracts from forward-looking opportunities to create protected areas that further commitments to reconciliation and protecting species at risk.

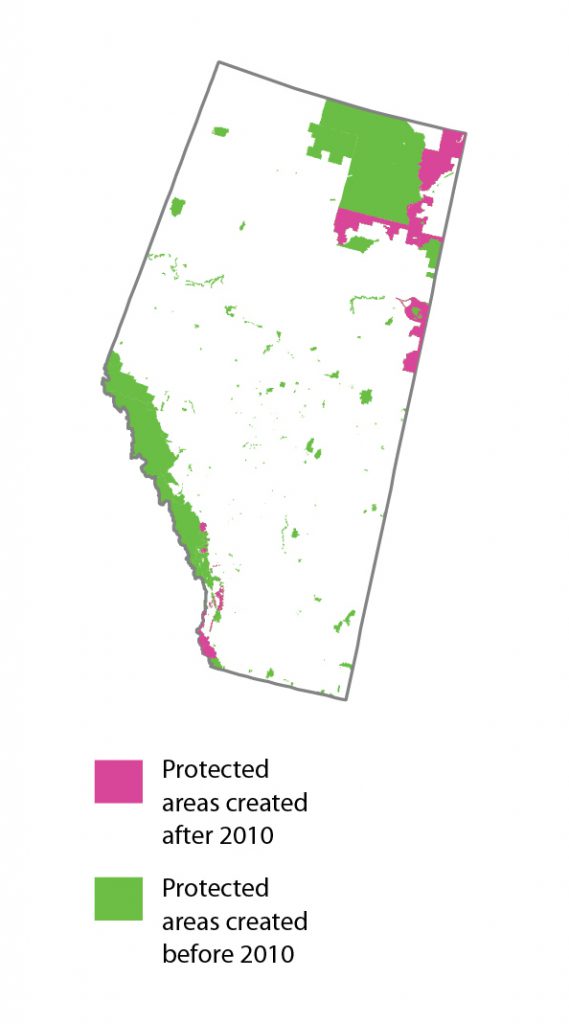

Alberta

Grade: F

While Alberta governments have created new protected areas, committed to protecting 17% of the province’s land and freshwater by 2020, and co-chaired the nationwide Pathway to Canada Target 1 process, the current provincial government has completely reversed progress by abandoning the 2020 target, undermining Alberta’s existing provincial parks system, and opening the Rocky Mountain foothills to coal development.

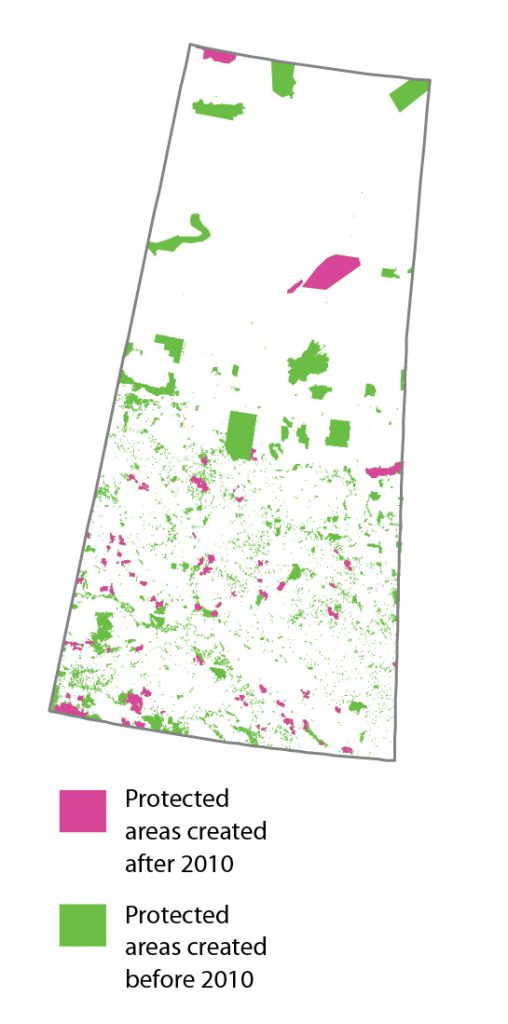

Saskatchewan

Grade: D

Over the past decade, the Government of Saskatchewan showed little ambition and achieved limited progress in protecting nature. The province only protected an additional 2% of Saskatchewan’s land base, falling well short of its 30-year-old target of protecting 12%. Saskatchewan also failed to put in place adequate conservation measures or management capacity to safeguard ecologically significant native grasslands that were transferred from the federal government. On a more positive note, Indigenous Nations are advancing proposals for large Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) with financial support from the Canada Nature Fund and are calling on the provincial government to support implementation of these initiatives.

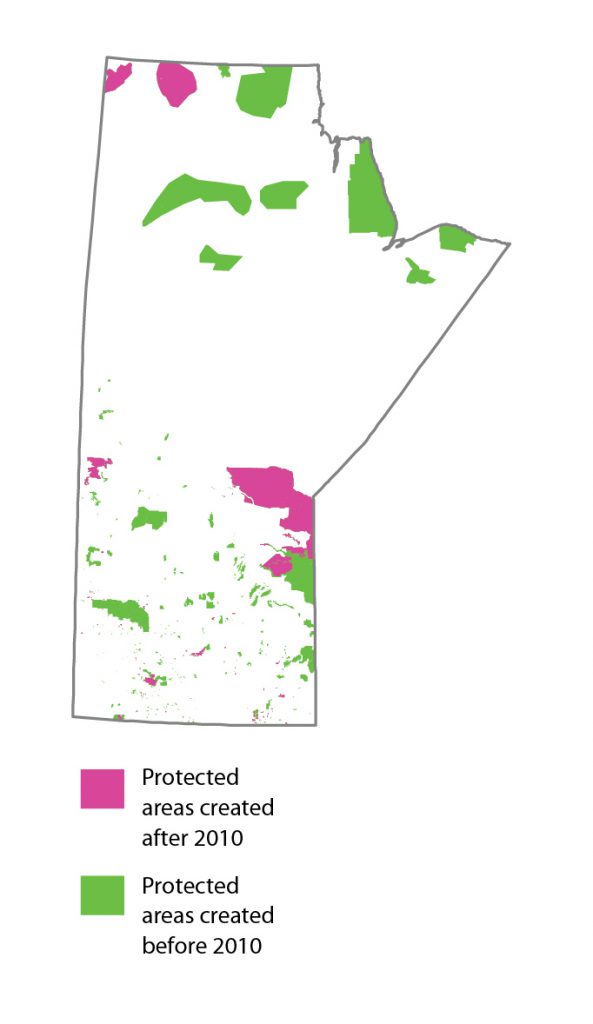

Manitoba

Grade: C-

While progress was made in expanding Manitoba’s protected areas prior to 2015, the provincial government protected just 177 km2 in the following five years. Worrying signs point to the province looking to identify “which assets should be divested” and seek “opportunities to decommission/transition parks to other models” (i.e. for other groups to operate or own parks). Meanwhile, Indigenous-led conservation initiatives and protected area proposals in Manitoba continue to move forward, offering a significant opportunity for protecting the province’s land and freshwater in a way that will contribute to reconciliation.

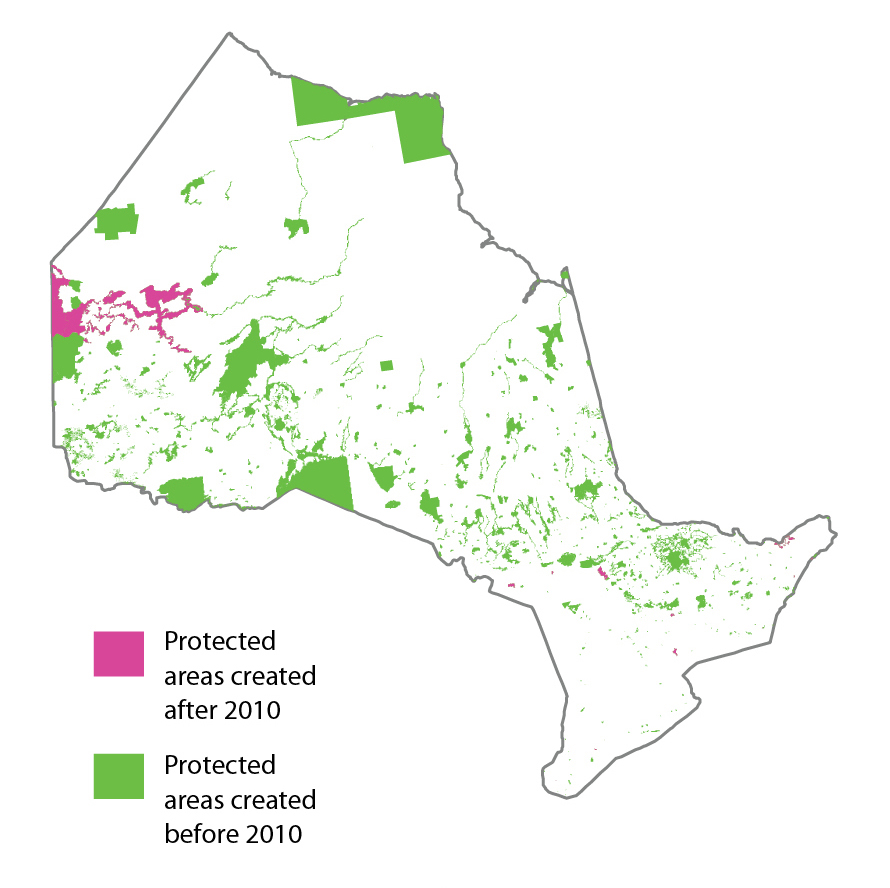

Ontario

Grade: F

The past ten years can be summed up as a decade of missed opportunities for conservation in Ontario. While a 17% land protection target was embedded in Ontario policy in 2012, the target was dropped in 2018. The province protected less than 1% of Ontario’s land base over the decade, and most of this progress occurred in 2011 as a result of First Nations-led land-use planning in northern Ontario. Since then, only eight small sites have been established, and no new protected areas have been reported since 2017. Meanwhile, the Government of Ontario has also dismantled or downgraded key elements of its environmental law and policy framework, including the Endangered Species Act and the Environmental Assessment process.

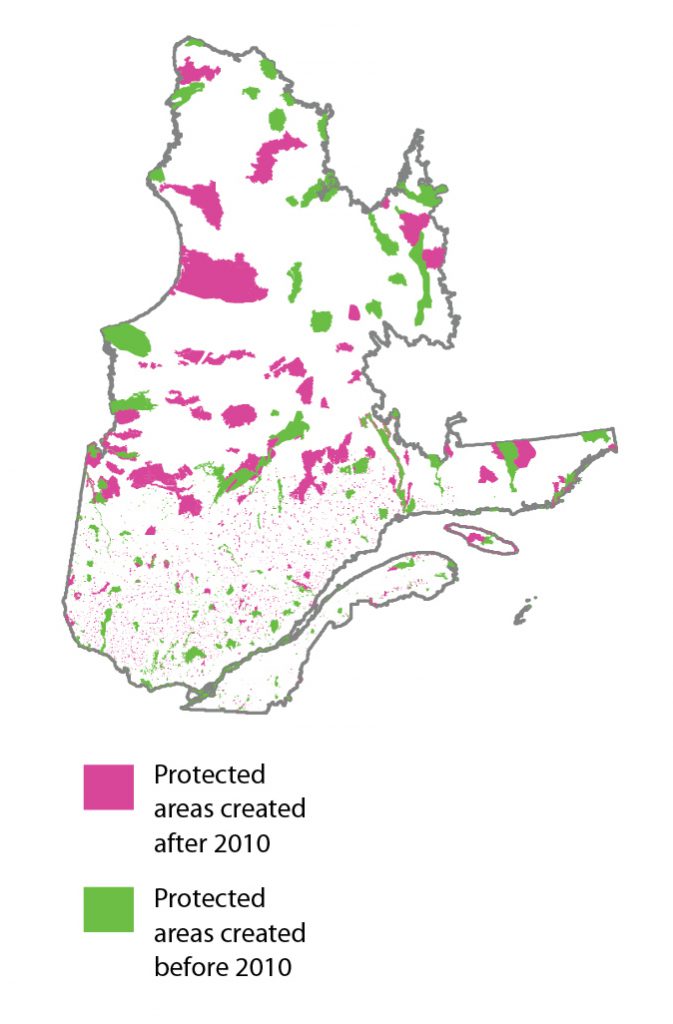

Quebec

Grade: A-

Quebec delivered on its promise to protect 17% of the province’s land and freshwater by 2020 through a major expansion of its protected areas network. While this is a significant achievement, many important sites identified for protection in southern Quebec still need to be designated.

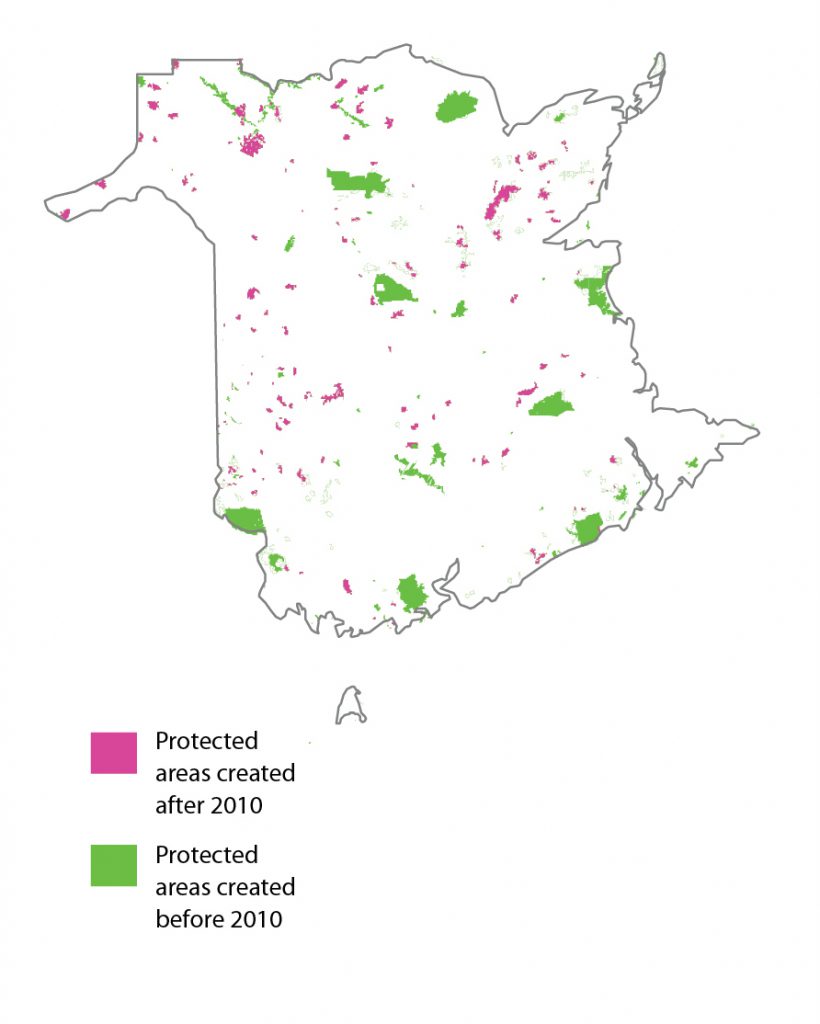

New Brunswick

Grade: B-

A recent commitment to double protected areas in the province, the launch of an extensive consultation process to engage the public, and relationship-building with Indigenous organizations for potential Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) move New Brunswick forward from the back of the pack. While the province still has a long way to go before its nature legacy is adequately protected, it is poised for a significant step forward.

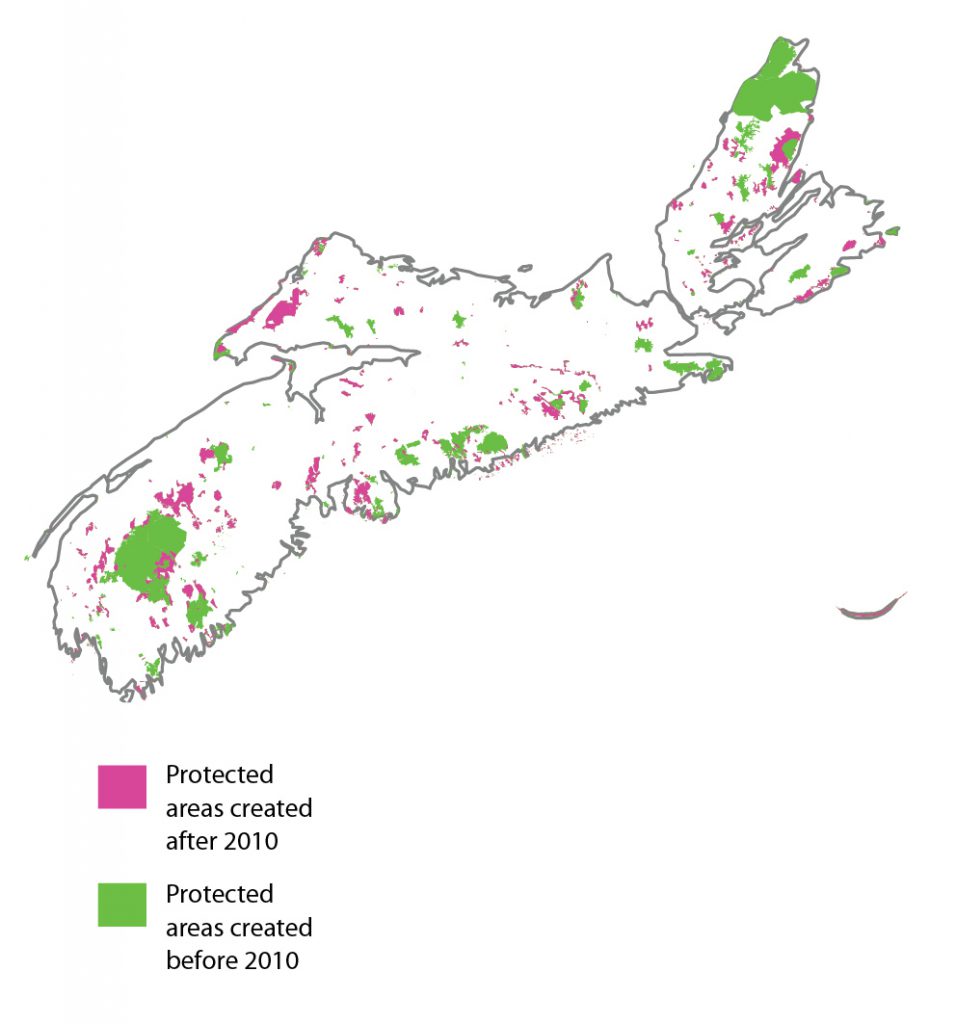

Nova Scotia

Grade: B

Nova Scotia has made considerable progress over the past decade creating new protected areas. Approximately 200 sites have received legal protection, with an additional 24 sites currently going through the public designation process. Within the past year, 91 sites have been announced for protection. This has increased the total amount of protected land in Nova Scotia by approximately 50% over the past decade. The Nova Scotia Our Parks and Protected Areas Plan, approved in 2013, identifies approximately a quarter million hectares of land for conservation. Most protected areas created in Nova Scotia, since then, are due to the implementation of this plan.

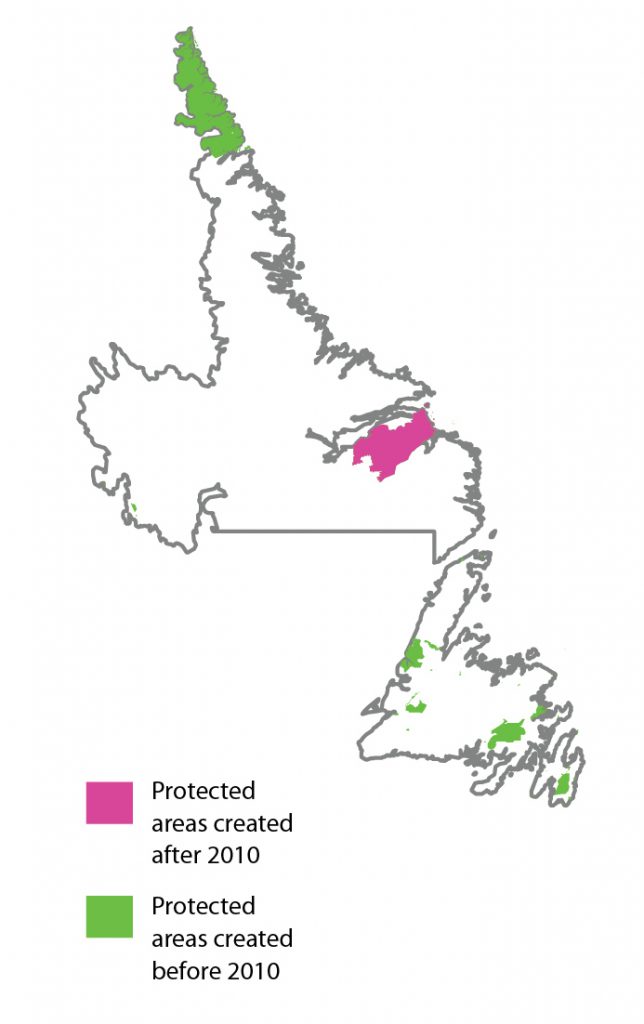

Newfoundland and Labrador

Grade: F

Newfoundland and Labrador made virtually no progress over the past decade in creating new protected areas and still ranks behind most Canadian provinces and territories in the percentage of land and inland waters protected. Only one tiny seabird site (Lawn Bay Ecological Reserve) was upgraded in status over the last decade. The province urgently needs to step up its work to protect important ecological and cultural areas, increase its focus and support for Indigenous-led conservation, and modernize its approach to site selection, including by engaging the public early in the process.

Prince Edward Island & Nunavut

CPAWS does not have chapters in Prince Edward Island or Nunavut. Given our lack of on-the-ground presence in these jurisdictions we are not assigning a grade for either government. Instead, we are offering an overview of each jurisdiction based on publicly available information about recent progress and opportunities to advance protection.

Prince Edward Island continues to make incremental progress on protecting land. In 2019, the province recommitted to achieving its decades-old target of protecting 7% of the island by the end of 2020. The province expanded its protected lands by 25% over 18 months but fell short of achieving the target on time. Private land protection and non-governmental land trust organizations continue to play a pivotal role in establishing protected areas on the island, and Indigenous-led initiatives are now also helping to drive progress.

Just over 10% of Nunavut is in protected areas, with many more protection opportunities identified through the Draft Nunavut Land Use Plan. Five new protected areas were established in the territory in the past decade, all through federal legislation. Five more conservation projects have been funded through the Canada Nature Fund, which should result in new IPCAs and other protected and conserved areas in the next few years.

- The Narwhal – B.C. holding out on federal conservation targets and large-scale protected areas

- Canada’s National Observer – 200 nature groups urge Trudeau to ‘get it right’

- Canadian Geographic – “We did this:” Is there a way out of our intertwined climate and biodiversity crises?

- The Narwhal – Where federal parties stand on Canada’s sexiest emissions fix: nature-based climate solutions

- The Narwhal – Where Canada’s federal parties stand on three big climate and environment issues ahead of the election

- The Hill Times – Provinces to blame for Canada’s broken international conservation promise

- Globe and Mail – A for Quebec, F for Alberta: Study rates Canadian governments on conservation

- The Narwhal – Ontario, Alberta get failing grades for conservation efforts

- National Post – A for Quebec, F for Alberta: Study rates Canadian governments on conservation

- Vancouver Sun – B.C. gets a C grade in protecting land and oceans: report

- La Presse – Le Québec premier de classe au pays, selon un rapport (Only available in French)

- Journal de Québec – Protection du territoire : le Québec premier au pays, mais doit faire mieux au sud (Only available in French)

- CBC The Current with Matt Galloway – New report gives some provinces an “F” for conservation efforts – Segment starts at the 37:00 min mark.

- CBC All in a Day with Alan Neal – CPAWS report card assesses why Canada failed to meet target to protect land

- Radio Canada Dans la mosaïque avec Alison Vicrobeck – L’Ontario fair piètre figure dans un rapport sur la protection du territoire (Only available in French)

- National Observer – Quebec and feds lead Canada’s conservation efforts

- Toronto Star – Quebec and feds lead Canada’s conservation efforts

- CBC News – Most provinces didn’t come close to meeting 2020 conservation targets, report says

- CPAWS Press Release (April 2021) – CPAWS welcomes largest Canadian investment ever in nature

- CPAWS Press Release (June 2021) – G7 leaders approve Nature Compact to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030

- CPAWS Economic Backgrounder – Investing in Nature Strengthens Our Economy

- Green Budget Coalition

- High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People

- Leaders’ Pledge for Nature

Contact Information for Media Inquiries

Tracy Walden

National Director, Communications and Development, CPAWS

twalden@localhost

613-915-4857